In 1952, at the age of 73, the author E.M. Forster moved into a set of rooms in King’s College, Cambridge as an Honorary Fellow, where he enjoyed the life of a feted author with few college duties. He was offered a ‘Companion of Honour’ in Queen Elizabeth II’s first New Year’s Honours list. Although previously he had turned down a knighthood, he now decided to accept a ‘CH’, he explained, because he preferred honours that came after his name.

The investiture was held at Buckingham Palace in February 1953, and Forster enjoyed every minute of it. When the young Queen told him what a shame it was that he had not written a book since A Passage to India in 1924, he politely corrected her. His collection of reviews and essays Two Cheers for Democracy had been published to general acclaim in 1951, he told her, and he had recently collaborated with Eric Crozier on the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd. (Alan Bennett imagines what the Queen might have thought of their meeting in his charming story, ‘The Uncommon Reader’)

Back in his college rooms, sorting through old family letters, Forster thought about his great-aunt Marianne Thornton and her posthumous influence. She had attended the newly crowned George III’s opening of Parliament as a child, something she never forgot, and lived through most of the nineteenth century. It was thanks to her legacy that Forster had been able to study at Cambridge, and later travel to Italy and become a full-time writer.

He decided to write about his great-aunt as a way of honouring her gift to him and exploring the historic links they shared. Marianne Thornton, published in 1956, connects and develops themes familiar from Forster’s fiction, including the loss of a beloved home, forbidden passions and second chances, and the final section is a moving account of his own young life, his only published memoir. It’s likely that, if she had ever managed to find the time to read E.M. Forster’s final book, Queen Elizabeth would have enjoyed it.

My thanks to Ann Kennedy Smith for her longer account on her website. The Queen and E.M. Forster – Ann Kennedy Smith (akennedysmith.com)

- Written by Anne Conchie

The writer Edward Morgan Forster lived at Rooks Nest House from 1883 to 1893, from the ages of 4 to 14. In later life he returned there often, as the guest of composer Elizabeth Poston.

His novel Howards End was inspired by his childhood home and its surrounding countryside. Forster’s writing is studied in schools, colleges and universities throughout the world. His work is concerned with themes that are still current today, including:-

- human relationships,

- conflicts of loyalty

- the need for connection between apparent opposites such as commerce and culture, poetry and prose,

He is constantly quoted in newspapers and has the distinction that one of his short stories is available in full on the Internet.

- Written by M.M. Ashby

Rooks Nest House, was a beloved home to both E M Forster and Elizabeth Poston. He lived there with his widowed mother during his young, formative years of four to fourteen and there, educated at home, he set deep roots, exploring the neighbouring countryside and developing an interest in gardening – including growing tall red poppies – especially enjoying identifying the local flora. In his earliest known teenage writings he said ‘the surroundings of the house were altogether very pretty, first and foremost the fine view’. His affection for his home was profound since it represented stability and security and so he was distraught when he had to leave it to be educated away, first in a boarding school at Eastbourne and finally as a day-boy at Tonbridge in 1893. His mother had socialised with the local gentry including Charles Poston and family, recently arrived at a nearby large Georgian Manor, called ‘Mallows’ but later renamed ‘Highfield’. The family made a lasting impression on the 7-year old Forster.

- Written by Anne Conchie

It has been said of the musician, Peter Warlock (nom de plume for Philip Heseltine) that he could not be understood if the girls in his life were ‘indicated only in the most shadowy way’. By the same token, we cannot fully understand Elizabeth without knowing more of her relationship with her friends, including the men in her life, particularly Phil, as she called him, around whom there had long been an atmosphere of mystery which Elizabeth herself had helped to maintain, consistently refusing, when asked, to talk about it in any detail.

At the time of her death, no correspondence between them was forthcoming and it was assumed that any such had been included in the material destroyed, at her instruction, by her nephew Jim Poston. Nothing between them was included within the collected letters of Peter Warlock published in 2005, although a short portion of one from Elizabeth to Warlock’s mother, written in February 1931 following his suicide the previous December showed that she had known him very well and that he was ‘fine & generous & great-hearted & all love & admiration for him only grow greater’.

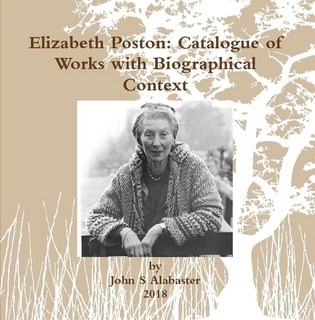

After a decade of work on the Poston papers, John Alabaster produced a glossy book encapsulating much of the previous works.

As the title suggests, it is a full list of works published or not, set in a biographical context. Though more expensive than earlier subsidised works, it is for anyone interested in her or neglected female composers of her era. It is available at Lulu.com page http://www.lulu.com/shop/john-alabaster/elizabeth-poston-catalogue-of-works-with-biographical-context/paperback/product-23663053.html#expand_text

- Written by admin